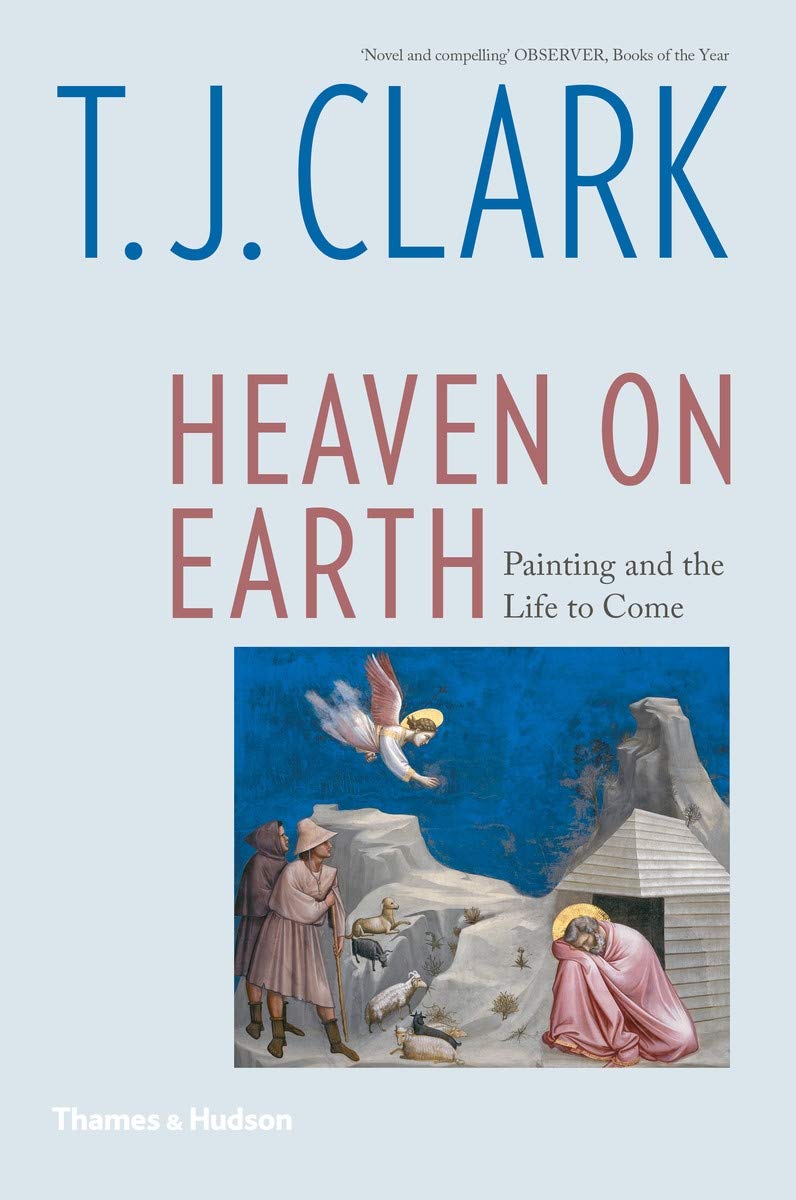

Heaven on Earth | T. J. Clark

Detalii Heaven on Earth | T.

carturesti.ro

122 Lei

Carte straina

Thames & Hudson Ltd

Heaven on Earth | T. - Disponibil la carturesti.ro

Pe YEO găsești Heaven on Earth | T. de la Thames & Hudson Ltd, în categoria Carte straina.

Indiferent de nevoile tale, Heaven on Earth | T. J. Clark din categoria Carte straina îți poate aduce un echilibru perfect între calitate și preț, cu avantaje practice și moderne.

Caracteristici și Avantaje ale produsului Heaven on Earth | T.

- Departament: gaming-carti-birotica

- Ideal pentru pasionații de jocuri, birotică și distracție online.

Preț: 122 Lei

Caracteristicile produsului Heaven on Earth | T.

- Brand: Thames & Hudson Ltd

- Categoria: Carte straina

- Magazin: carturesti.ro

- Ultima actualizare: 27-10-2025 01:24:43

Comandă Heaven on Earth | T. Online, Simplu și Rapid

Prin intermediul platformei YEO, poți comanda Heaven on Earth | T. de la carturesti.ro rapid și în siguranță. Bucură-te de o experiență de cumpărături online optimizată și descoperă cele mai bune oferte actualizate constant.

Descriere magazin:

One of the world s most respected writers on art investigates the very different ways painting has given form to the afterlife.The idea of heaven on earth haunts the human imagination. The day will come, saybelievers, when the pain and confusion of mortal life will give way to a transfiguredcommunity. Such a vision of the world seems indelible. Even politics, some reckon, hasnot escaped from the realm of the sacred: its dreams of the future still borrow theirimagery from the prophets. In Heaven on Earth, T.J. Clark sets out to investigate thevery different ways painting has given form to the dream of God s kingdom come. Hegoes back to the late Middle Ages and Renaissance to Giotto in Padua, Bruegel facingthe horrors of religious war, Poussin painting the Sacraments, Veronese unfolding thehuman comedy. Was it to painting s advantage, is Clark s question, that in an age ofenforced orthodoxy (threats of hellfire, burnings at the stake) artists could reflect onthe powers and limitations of religion without putting their thoughts into words?At the heart of the book stands Bruegel s ironic but tender picture of The Landof Cockaigne, and also Veronese s inscrutable Allegory of Love. The story ends withPicasso s Fall of Icarus, made for UNESCO in 1958, which already seems to signal perhaps to prescribe an age when all futures are dead.

Produse asemănătoare

Pure Land: A True Story of Three Lives, Three Cultures and the Search for Heaven on Earth - Annette Mcgivney

![]() libris.ro

libris.ro

Actualizat in 28/10/2025

111.32 Lei

The Lamb\'s Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth - Scott Hahn

![]() libris.ro

libris.ro

Actualizat in 28/10/2025

139.5 Lei

What On Earth Is About To Happen For Heaven\'s Sake: A Dissertation on End Times According to the Holy Bible - Kent E. Hovind

![]() libris.ro

libris.ro

Actualizat in 28/10/2025

383.62 Lei

The Honeymoon Effect: The Science of Creating Heaven on Earth - Bruce H. Lipton

![]() libris.ro

libris.ro

Actualizat in 28/10/2025

111.55 Lei

Worship on Earth as It Is in Heaven: Exploring Worship as a Spiritual Discipline - Rory Noland

![]() libris.ro

libris.ro

Actualizat in 28/10/2025

148.74 Lei

Produse marca Thames & Hudson Ltd

Store Cupboard Genius. 200 clever recipes to transform your forgotten ingredients, Hardback/Anna Berrill

![]() elefant.ro

elefant.ro

Actualizat in 28/10/2025

144.99 Lei

The History of Western Art, Paperback/Janetta Rebold Benton

![]() elefant.ro

elefant.ro

Actualizat in 28/10/2025

79.99 Lei